Karen, what was your life before finding yoga?

Life before yoga involved the arts — drawing, drawing, and more drawing, all through childhood and high school, visual art as an undergraduate (sculpture, specifically) and creative writing (poetry) in graduate school. I had no interest in physical pursuits — it was all art, all the time. That was my east coast life. Grew up in Boston, hanging out with artists and musicians and writers, then on to New York, where everyone drank espresso and smoked cigarettes and plotted how they were going to get out of New York. My daughter Anna was almost two years old when my then-husband received a job offer in Scottsdale. It was a good time to get out of New York — the end of the 80s. We spent a couple of years in the desert, which I immediately fell in love with before we moved to the Bay Area for another job opportunity. He had the job, I raised Anna, worked part time in bookstores, and taught writing classes.

I also hung out with my brother Nick a lot. He managed a gym in the Castro in San Francisco, and he talked me into learning weight lifting. Old school weight lifting — no machines, all free weights, etc. He was an awesome teacher — I still remember a note he sent me about why the lift I was most resistant to (stiff-legged deadlifts!) was exactly the thing I most needed to do. I fell in love with the meditative aspects of lifting and learned that I could do so much more than I ever imagined I could. Then everything came tumbling down: my brother was diagnosed with HIV, a death sentence in those days. His friends died, his boyfriend died, and then he died. At the same time, my marriage collapsed. In 1996, I found myself a grieving, divorced, single Mom with a bookstore job who taught a few creative writing classes. Weightlifting was my solace, my daily discipline, and a way to stay connected to my brother. In my grief, I turned to Zen, something I’d toyed around with since my early 20s.

Needing to make more money to support my daughter, I went back to school for educational technology and started working in a corporate environment. I also took the first opportunity to return to the desert. Anna and I returned to Phoenix at the end of 1999. I kept my lifting practice, but I also fell in love with rock climbing. I lifted at the gym every day, climbed on the weekends, and practiced zazen at a local zendo, with Sokai Geoffrey Barratt. One morning, on the third day of a retreat, I asked Sokai why, despite the fact that I was fit, it hurt so much to sit zazen. His fateful and generous answer: “You need to go to the Indians — they’ve figured this out.” So at the behest of the abbot of my zendo, I looked into yoga classes.

And what came about from the yoga classes?

The first class I took was with my daughter. She wanted to give yoga a try. I went to the gym to work out first since I figured class would just be some stretching. I clearly remember finding myself later that afternoon in a prolonged down dog, sweating and thinking, “This is really *hard*!” Lesson learned. Scottsdale had a local yoga place that offered all kinds of classes, so I tried a bunch of things: flow designed to make your muscles burn, flow with the loud music, hot yoga, hot yoga with louder music, power, power with hip hop music, yin. I did not like the music and I definitely didn’t want any of the “yoga and wine” or “yoga and chocolate” experiences that were popular at the time. From what I could tell, yoga classes seemed to be designed to be workouts — and I could be more efficient just going to the gym. I loved the repetition of lifting — every rep a new chance to breathe more fluidly and move more efficiently, over and over again. So the randomness of movement in yoga classes wasn’t really doing the trick for me. Over the years, as I juggled a daily gym session and daily meditation, I’d always fantasized about some magical solution that would combine both physical and spiritual practices. I’d hoped yoga might be that solution, but the classes I tried weren’t a replacement for the gym, and they definitely didn’t compete with sitting meditation. But yoga was a good stretch for climbing, so that’s what kept me going.

Eventually, I got curious about the “ashtanga” listing in the Studio menu. I asked about it at the front desk, and the folks there seemed a bit taken aback as if I was asking about something intense and mysterious. They didn’t know a lot about it but said it was a set sequence. “Do I need to know the sequence to go?” I asked. They said they didn’t know, but it was probably a good idea. So I got Richard Freeman’s primary DVD and set off to learn enough to go to class. I really liked the DVD, because I loved Richard Freeman’s language, and because the practice was precise and orderly and challenging. I practiced with the DVD until I had a rough idea of what to expect in class, and on the weekend after the Fourth of July in 2005, I screwed up my courage and went to a led primary class.

The class was taught by Dave Oliver. Dave spent more than ten years practicing with Prem Carlisi, and when he was traveling up and down the California coast during his semi-professional beach volleyball career he practiced with Tim Miller in Encinitas. Dave taught a popular led primary class in Scottsdale every Saturday morning. He also offered led classes a few times during the week. I was in love with the practice before I even finished that first class. The breath, the vinyasas, the challenge of the postures, the amount of concentration required — it was like a huge, brand new novel: full of surprising things that would take me a very long time to explore. And it was so much fun, kinesthetically.

I started going to all of the led classes Dave offered. One morning, when only two of us showed up for class, Dave asked me, “Have you heard of Mysore practice?” I had because I’d done some research online. “We’ll do that today,” he decided. Then he said something I’ll always remember. “Led makes your body strong,” he said, “and Mysore makes you strong here,” as he tapped his brow. I had no idea what I was doing, but I bravely moved forward in my first Mysore practice — completely butchering the sequence.

Quite soon after I began, Dave moved the practice from the studio to his house — in a little room between his garage and laundry room. I found myself driving in the early morning darkness to an almost stranger’s house to do a practice that captivated me for reasons I couldn’t quite articulate. I chanted the Vande and names of the asanas of primary as I drove because, for some unfathomable reason, it was very important that I learn all of it correctly.

It sounds like the pull of the practice began drawing you in. What happened at this point to your first trip to Mysore?

I kept practicing with Dave and followed him as he moved around to different venues: a little space downstairs from a tanning salon, upstairs in a rock climbing gym. I went to his Mysore class the three days he offered it: Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and took his led class on Saturday. On Tuesday and Thursday, I practiced alone in the tiled foyer of my house. A year and a half into my practice, Dave decided to discontinue his Mysore program.

Losing my teacher hit me with surprising force. I felt like an ashtanga orphan. I understood why he stopped teaching, but that didn’t make me feel less panicked and cast adrift. It didn’t take long before I figured out my next step: instead of trying to find a new teacher right away, I was going to learn how to do full-time self-practice. That way, I could be self-sufficient no matter what happened in the future. For support, I had my online friends. In the mid- to late-2000s, there was an explosion of ashtanga bloggers. There was an aggregator site, ashtangi.net, and that’s where I “met” and built friendships and a support system with lots of practitioners — both home practitioners like myself and practitioners who went to shalas — from around the country and around the world. There was also the ashtanga ezboard, a discussion site that still exists as an archive with lots of excellent technical information.

Any time I traveled, whether for work or for vacation, I’d research teachers in the area and visit their shala. I remember getting in a cab at 4 AM in Singapore and handing the driver who spoke no English a piece of paper with an address scrawled on it. We drove in the early morning darkness until he pulled up to a curb and pointed at a building. Sure enough, once I got inside, I found people starting their morning practice and was welcomed in. Same thing in Washington, D.C., Minneapolis, Seattle, London — early morning darkness, trying to find a location, and then the welcoming light of a warm Mysore room. You know, as I think about this, I realize that those trips to different Mysore rooms are a good analogy for any spiritual undertaking: making my way in darkness to some unfamiliar and sometimes frightening location, trusting that the journey would be worth my while, and having faith that the outcome would be good. And in all of these places, I met dedicated and devoted practitioners — many of whom have become close friends.

Daily home practice with occasional visits to shalas or workshops went on for four and a half years. I longed for a teacher, though. I wanted clear direction for my practice. From the very beginning, I’d been interested in correct method — my interests in art, both visual and written, had always revolved around attention, precision, and exploration. Weightlifting and climbing introduced the added dimensions of breath, movement, and fear. I’d always relished the fine points of technique — both physical and mental — which leads to focus and ultimately (per zen) to stillness. I wanted to get to the heart of practice. I wanted to get to the place where the form is emptiness and emptiness are form. I decided it was time to go straight to the source: Sharath.

And what was your experience visiting the source? Walk us through that experience.

I think anyone who’s been to Mysore will tell you that there is no way to really share what it’s like. I kept a blog through my first five trips (https://journeytomysore.wordpress.com), where I tried to detail what it’s like to be there, but in the end, you really just have to experience it. Anyone who has built up some tapas, some fire in their belly for the practice, should go. It’s not about proficiency — there isn’t some standard of physical practice that must be met in order to be ready to go. It’s all about desire — willingness to bring yourself halfway around the world because there’s something there that you know you just have to experience. Something that causes you to disregard doubt and fear and any obstacle. The desire that gets someone to start practicing in the first place, multiplied by the tapas that builds up after a good dose of daily practice — that’s the impulse that gets you to Sharath’s doorstep in Mysore.

My daughter Anna traveled with me on my first trip. She’d just finished undergrad, and I wanted to spend some time with her before she headed off into her adult life, so we spent a month in Mysore. I think Phoenix may be as far away from Mysore as you can get on the globe, so after a good 24 hours of planes and layovers, followed by a four-hour swerving, beeping drive in a hired car that sped through a night landscape chock-full of run down buildings and remote villages, dogs and cows, people and random open-all-night-even-though-no-one-is-around chai stands, we found ourselves in our apartment. I put down my suitcase and immediately panicked, thinking, “Oh my God, what have I done?!”

Within an hour of arriving, as Anna got a bit of sleep, I heard “Karen! Karen!” from under our second-story window. How could someone know where I was, when even *I* didn’t know where I was? It was my friend Angela from Ann Arbor, ready to take me for a quick scooter tour of the area. The tour was a blurry whirlwind, but the presence of a friend made all the difference in the world. Later that afternoon as Anna and I walked down the street toward the main road, I saw a figure approaching. Sure enough, it was Susan, a friend I’d “met” online and whose shala I’d visited when I traveled to London. Mysore is a small world. It’s a place where you come together with people from around the world who you interact with online or at shalas, people who primarily exist in your ashtanga reality – your sadhana reality – and suddenly they’re the people all around you at practice and at cafes when you go out for meals or coffee, or just walking down the road. It’s very powerful — a convergence of worlds. It’s almost like a dream. And the central figure, Sharath, is at the very epicenter of your daily reality.

I loved being in the shala with Sharath from the first moment. It was terrifying, of course, to be in that room I’d only seen in photographs. Under huge pictures of Guruji and Amma, Sharath called us one by one into the room and expected us to respond quickly. There were statues of the gods on the altars, and images of Krishnamacharya, Brahmachari, Shankaracharya. The floor was covered with a layer of old cotton rugs, so it was a riot of colors and patterns, and the windows were open to street noises — street vendors shouting, dogs barking, cars and trucks honking. So much sensory input! By the time I was called into the room, I was a ball of adrenaline and pre-practice caffeine and raw synapses. I look back on it now and realize that I was only six years into daily practice — the drama of the travel and being in the shala far outstripped my ability to automatically settle into practice. I did my practice, of course, but my mind was far from deeply sunk into it. When I came up from my first dropback, I was stunned to find Sharath standing on my mat, mere inches away from me. “Oh!” I said, “You scared me.” He deadpanned and said, “That is why I come here. To scare you.” And then he laughed. What could I do except carry on with the rest of my dropbacks? My mind was turned up to eleven, I can tell you that. Sharath’s presence pulled me directly into the center of the present moment — a place where the previous moment and the next moment simply did not exist. And he just stood there in complete patient stillness while I thrashed around (in my mind, at least) trying to catch my bearings, completely unmoored. What in the world?!?! My body did the dropbacks, even as I had a wordless lesson in how my mind was not controlled.

Every trip I’ve taken to Mysore seems to have a theme that reveals itself over the course of time spent there. The theme for the first trip was lack of control. I couldn’t control my environment – India is huge and chaotic; the energy of the shala is like a tsunami; Anna and I were lost as soon as we walked out of our apartment; we didn’t know how to do simple things like negotiate the price of a rickshaw ride or find a hospital when she had an allergic reaction to ant bites. We muddled through, but to harbor the illusion of having any mastery or control whatsoever is the height of absurdity in Mysore.

Guruji and and now Sharath, place such heavy emphasis on “correct method.” How and why is this so important to the practice from a student and teacher perspective?

Guruji and Sharath have spent decades observing the experiment of tristhana. Research design calls for parameters, and adhering to correct protocols and practices frees us from biases and flights of fancy — all of the preferences and aversions that crop up. “Freedom in discipline” is exactly the right way to characterize it. The correct method is exquisitely simple. But our minds are so consumed with projecting into the future or clinging to the past that we can’t focus. So, like good researchers (and good teachers!), they’ve given us a research design that requires that we not muck around with variables. Otherwise, we invalidate our results.

The correct method is important to students because, without it, it is incredibly difficult to harness the mind — even the smallest deviation can be a huge distraction. It’s not the deviation itself that’s the issue — deviations are neither good nor bad. It’s the act of deviating that’s the problem. As Seung Sahn used to tell his zen students: “Only go straight.” Once you introduce options and variety, the mind goes on a spree entertaining itself — a thinking and imagining and wishing and projecting bender, if you will. Mind loves to do that, and the whole purpose of the practice is to bring that under control.

Correct method is important for teachers because once you’ve been at it long enough that tapas, svadhyaya, and isvara pranidhana are fully integrated and unshakeable, you can help others who want to follow the path, who want to integrate the system into their bodies and minds and spirits. As a teacher, you have to be steady in the method: the pressure to doll it up so it’s exciting and competitive with other yoga “products” on the market will be great — but if your students don’t learn that the tapas of mundane daily practice is really what it’s all about, you’re doing them a huge disservice.

How has their teaching influenced you? What are your guiding principles as a teacher?

I haven’t been directly influenced by Guruji, though I have strong feelings about him through stories Sharath shares. I didn’t start going to Mysore until after Guruji passed away. It was a dramatic time to start going to the shala: Sharath was transitioning to be a leader. I’m interested in leadership, so I feel really lucky to have been around during those years.

Over time, as I’ve studied with Sharath, I’ve been influenced by his work ethic. Maybe that seems a rather mundane characteristic to start with, but it astonishes me that he can be fully present day after day for hundreds and hundreds of people. And do his own practice. And be devoted to his family. His stability is a huge inspiration for me. The behavior he models helps me understand how to behave — in my shala, in my day job, and with my family.

My practice with him over the years has certainly changed. The lessons have evolved and grown increasingly subtle and progressively less physical. How does he transmit this stuff?!?! It’s quite mysterious to me, and I’ve come to a point where I’m not trying to figure it out. My technical background is in the design of education, so pedagogy is in my wheelhouse, but there’s stuff going on here that defies explanation.

The principles that rise out of studying with him — which are my guiding principles as a teacher — are simple. Basically, it’s this: model the behavior I believe in and that I expect from others (yamas, niyamas), practice what I preach (meaning: practice practice practice, and then practice some more), always be ready to laugh, and recognize that all I can authentically share is what I’ve experienced over the course of my own practice and in my studies with my teacher.

This practice refines over time, and shifts from the realm of performance into the realm of concentration and contemplation. It is deeply intimate and completely impersonal simultaneously, which is something I find endlessly thrilling. The physical is always there, of course, and there’s exquisite joyous energy in the physical, but in the end, we’re not headed toward physical mastery — the asanas are tools and the mastery simply a byproduct. The end game is controlling the mind. All I want to do is help people stoke the tapas to keep going in practice until the surface of the physical cracks and ksana tat kramayoh samyamad (meditation on moments in time and their sequence) kicks in.

Can you recount a time where you encountered doubt?

As soon as I saw this question, I asked my husband to reality check me. I asked him what he thought of when he thought about my relationship to doubt, over the course of the past twelve years of practice. He said: “I remember you dealing with physical struggle, but doubt is a mental thing, and I don’t recall any doubt.”

I don’t have asana doubt, which is what he was thinking about, but I have existential doubt, for sure! There’s a saying that the four prerequisites for practice are great faith, great doubt, great vow, and great vigor. When I first went to Mysore it was because I wanted to see if being there and studying with Sharath would satisfy the questions in my mind about practice. About this thing that I felt driven to do, but didn’t understand exactly why.

I thought I was looking for someone in whom I’d place my faith. And I’m not going to lie — the idea of placing my faith in a person made me uncomfortable. Years of being an atheist and a Buddhist made me very skeptical of faith. Clearly, there was some faith at work to drive me to practice every single day. Over the course of the next few years of traveling to India, I had experiences that helped me realize that faith isn’t something you place “in” someone. It’s a bedrock principle, like a mountain rising out of the earth. It just is.

Buddhists rarely speak of Buddhism as a “faith.” Instead, it’s a practice. Faith is part of the practice, and so is doubt. Doubt is envisioned as a hot iron ball stuck in your throat that you can neither swallow nor spit out. It’s the question that brings you to practice every day, the question you can’t answer.

My zen teacher, Sokai, passed away a couple of years ago. I miss him. He used to call me after every trip I took to Mysore. I’d tell him about my travels, and then ask him the questions that my trip had stirred up. I remember asking him, “Why is there suffering and death?” Big questions that stick in your craw — that’s doubt. Doubt about our purpose, our lives, the world. Things we can’t fathom or solve. We come to practice because of them.

So you’ve not had a major injury or setback in the Ashtanga practice that questioned the path you’ve chosen or the sacrifices required?

I haven’t. I was accustomed to long-term daily practices (creating visual art, writing, weightlifting, climbing, zazen) before I came to Ashtanga, so I had the part about just practicing and not perseverating dialed in. I love having something that really absorbs me, and I’m pretty steady by nature, so I never spent much time worrying about my path or thinking about sacrifices. I trusted that it would eventually come clear to me if it were the wrong path. And as far as sacrifices go, I don’t feel like I’ve sacrificed very much at all — I’ve received far more from the practice than I’ve given.

I’ve only had a handful of minor injuries. Early on in my practice, I felt a bit of self-pity about being a home practitioner, figuring that if I had access to lots of adjustments, I’d “progress” more quickly. Now I wonder if my situation didn’t contribute to the good luck I’ve had on the injury front. As a teacher, I definitely fall on the “less is more” end of the adjustment continuum.

That said, everyone has struggles and doubts. When students struggle, I try to get them to take a broad view. This is a lifelong practice, so of course, things will come up. The beauty of the practice is that it patiently teaches over and over again that anything you feel is okay, and it’s transient, and none of it is “you.” The practice is simple, direct, obvious, and literal. It’s also paradoxical, poetic, and deeply personal. All you have to do is show up, trust what you don’t know, and enjoy the ride.

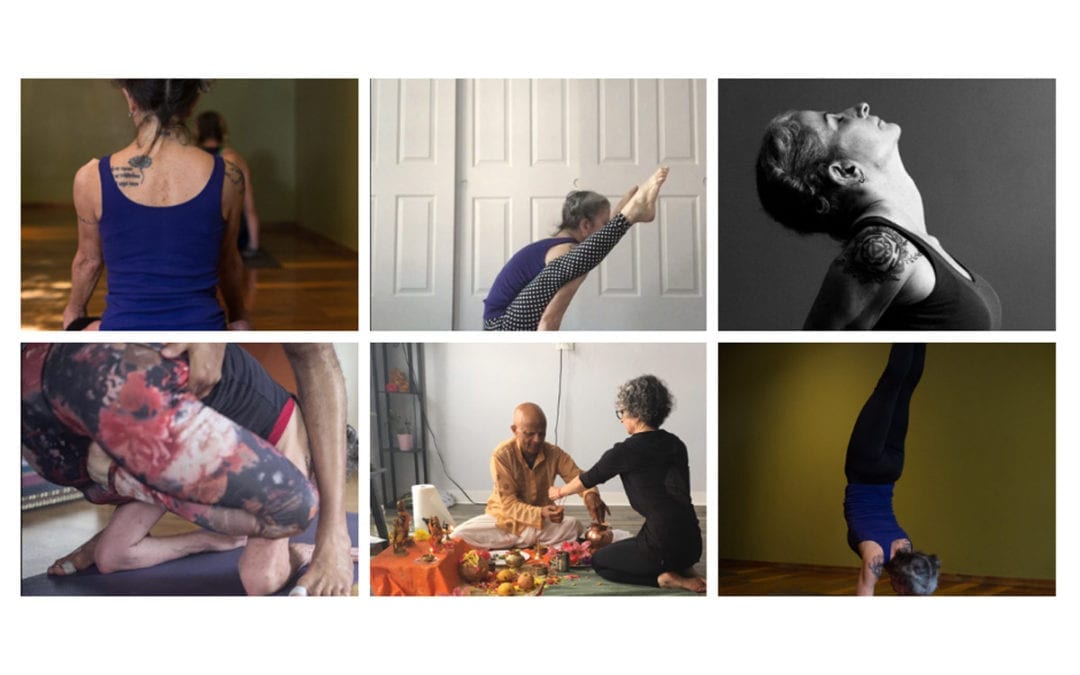

You’ve recently opened up a new shala space. Walk us through your vision for it.

I have opened a shala! Mysore Phoenix. It was kind of a surprise, even for me. This March, just after I’d come back from Mysore, I was on a business trip, practicing in a hotel room in Chicago, and it dawned on me that I had lots of information from the preceding month with Sharath, and no place to share it.

My vision for Mysore Phoenix is that we are a traditional shala. For dedicated students who want to build a sustainable daily practice. We have minimal infrastructure and a minimalist space — an environment with as few distractions as possible. My goal is to share what I’ve learned from Sharath, as simply and directly as I can.

The shala is here to support students and learning. The energetics, for myself and for the students, is not “What am I getting?” but “How can I contribute?” The goal is a student body committed to developing their own practices and supporting the practices of their fellow students. No products or marketing beyond just informing the world that we exist, and no other distractions. I don’t judge the progress of the shala by numbers of people or amounts of money, but by whether the practice is making good things happen for students. Are they steadier? Stronger and more flexible mentally? Are they manifesting good things in their lives? These are the outcomes I’m really interested in. “Not a lot of bling, but a whole lot of continuity” is how a good friend has characterized her shala. I’m taking that as a model.

On the Mysore Phoenix altar, along with pictures of Sharath and Guruji and Amma, is a picture of Sokai. I want to honor his devotion to sadhana in his small zendo in Phoenix. Every morning and evening, he sat in the zendo. Whether people came to sit or not, he did his practice. I love the commitment to being present, being steady, being devoted. Mysore Phoenix welcomes people who want to manifest those values.

Do you practice before you teach each day and is it critical to do that before assisting your students?

I always practice before teaching. It is part of this sadhana, and the most critical promise you make when you commit to having students. It is the heart of the Ashtanga method, and why I respect this system. If I don’t practice, I am teaching what zen calls “dead words.” Living words spring out of the heart and out of the moment. Dead words come from your mind — they come from the past, from what you think is true, from what someone else told you, instead of from what you are experiencing in your own practice and in this very moment. In order to teach something that’s living, I have to be grounded in the present moment. What I teach has to come from the direct experience of a long-term daily practice. That’s how we roll in Ashtanga, and it’s an ethical system that I really respect.

Any final thoughts?

In our practice, the paradox is this: You can always practice harder (and should), AND at the very same time perfect, complete practice is always – and instantly – available to you this very moment.

Students think practice is about bodies. But our bodies, like asanas, are tools. Practice hard to wake up.

SOURCE: ashtangaparampara.org

[* Shield plugin marked this comment as “trash”. Reason: Failed GASP Bot Filter Test (comment token failure) *]

This brought tears to my eyes. Thanks for the experience (that’s also so well written)!